An improving U.S. economy and growing job market are making it more difficult for the Federal Reserve to justify its policy of near zero interest rates, Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser said Friday.

Mr. Plosser said he is keeping an eye on the recent drop in inflation, but argued central bank officials should look past it since most of the decline is attributable to sharply falling energy costs

Cheaper energy is “unambiguously positive” for the U.S. economy, Mr. Plosser told CNBC television in an interview.

“We’re getting to the point where it’s hard to justify not raising rates,” said Mr. Plosser, who will retire next month. “There’s a good justification for increasing rates earlier.”

The Fed brought official borrowing costs to zero in December 2008 and embarked on three rounds of bond buys to support economy growth and recovery. Mr. Plosser has often been a skeptic of the Fed’s more aggressive moves.

Late last year, Mr. Plosser dissented against the Fed’s decision to say it would remain “patient” in raising interest rates because he feared policy makers would be tying themselves down to specific dates rather than following the data. The Fed is expected to begin raising interest rates at some point this year, but the exact timing remains a subject of avid debate.

“The committee will have to figure out how to transition away from ‘patience,’” Mr. Plosser said.

Friday, February 6, 2015

Fed’s Plosser: Getting Hard to Justify Not Raising Rates

We Ignore Unintended Consequences At Our Peril

by Adam Taggart

Early in my business career, I was faced with a challenge that gave me an appreciation for a critical lesson about life and business. It's that oftentimes, even with the best of intentions, our actions create consequences completely different from what we intend.

It's that insight that makes me so concerned about the grand central banking experiment being conducted around the globe right now. With little more than a lever to ham-fistedly move interest rates, the central planners are trying to keep the world's debt-addiction well-fed while simultaneously kick-starting economic growth and managing the price levels of everything from stocks to housing to fine art.

As with an earlier article I wrote focusing on the Bullwhip Effect phenomenon: the complexity of the system, the questionable credentials of the decision-makers, and the universe's proclivity towards unintended consequences all combine to give great confidence that things will NOT play out in the way the Fed and its brethren are counting on.

A Puzzle To Solve

Two years after graduating business school, I joined the team at Yahoo! Finance as its Marketing lead. It was a crazy time there; the tech bubble was in mid-burst and advertiser dollars -- the main source of revenue for the business unit -- were fast drying up. We went through several general managers within my first year there as the leadership scrambled for a sound course to chart.

Amidst the turmoil, a lot of misfit projects were tossed in my lap. Partly because I was the "new guy" and least likely to refuse, but mostly because the engineering-driven culture there didn't quite know what to do with a marketer, so any square peg looked like fair game.

One of those projects was the Yahoo! VISA card. A few years before my arrival, VISA approached Yahoo! with an idea everybody thought a winner: Our credit card + your massive audience = lots of money to be made. So a snazzy purple card was minted, which Yahoo! committed to promote with a certain chunk of its prodigious banner ad inventory.

By the time the project fell to me, I was told that things weren't working out to either party's hopes. VISA was disappointed and Yahoo! felt it wasn't getting enough money in return to merit the value of advertising inventory it was blocking off. But no one seemed to have any details to share. Apparently things had been running mostly on autopilot, with no one held accountable for oversight. So, I started doing a little digging.

On the Yahoo! side, I made sure the ads were running in the channels of our network where we knew "people who spend money" were most likely to be: Finance, Real Estate, Shopping, Autos, etc. We were also using targeting profiles that looked for users in favorable demographics (peak earning ages, high-earning professions, affluent zip codes, etc). So, it seemed our marketing plan was sound, and indeed, the click-through rates on the ads were well above normal. We were sending a lot of leads over to VISA.

Things got murkier when talking with the VISA folks. "The quality of your leads is terrible", they told me. Which puzzled me at first. I double-checked the data and confirmed the demographics of the people targeted by the ads were solid -- substantially better, in fact, than the median Yahoo! user. And Yahoo!'s user base was so vast, there was no reason to suspect it should be materially different than other mass market audiences VISA marketed to.

So if our audience was good, and our ads were generating plenty of leads, why was our relative performance so much worse?

Attracting The Undesirable

The 'aha!' moment came once I learned why our leads were getting rejected. Their credit scores were terrible.

This was something I was blind to when running my ads on Yahoo!. I could see what a user was interested in (for example, stocks), I knew he was a 45-54 year-old male living in a zip code that had an average household income of $100,000 (say, Newport Beach, CA), but I had no ability to know if he managed his finances wisely or not. He could be up to his eyeballs in debt, and he'd look no different to me than his debt-free neighbor.

So for some reason, all the reckless spendthrifts were responding to my ads much more than the prudent savers. Why? I wondered.

And then it hit me: this was a classic example of adverse selection.

Think about it for a moment. What do you often see when you open up your mailbox? A bunch of offers for credit cards. Who doesn't get those? People with bad credit.

And if you have bad credit, chances are your finances aren't in great shape. Meaning: you'd sure like some credit if you could get your hands on it.

So, those were the people who were thrilled to see the banner ads I was serving, and who rushed to click on them and apply for the card.

The entire 'win-win' strategy originally struck between VISA and Yahoo! was failing due to a massive unintended consequence. The people we least wanted to respond to the offer were in fact the ones most motivated to do so.

Acknowledging The Reality Of Unintended Consequences

I see a lot of similar unintended consequences in the strategies that the Federal Reserve and its central banking brethren have been pursuing over much of the past decade.

The global financial system wants to correct via natural market forces, due to slower economic growth and excessive debt levels around the world. But the central banks have decided to thwart nature by intervening to prop up insolvent institutions and reduce the cost of debt, all in hopes of buying enough time for the system to grow out of its woes.

But nearly 7 years after the 2008 crisis and $Trillions upon $Trillions in stimulus, where are we? With moribund economic growth and an ever bigger wealth gap than ever before, as this recent video explains:

Quite simply, the strategy is not working out according to plan.

And very likely compounding these unintended consequences is the basic principle of uncertainty. In his article Why Our Central Planners Are Breeding Failure Charles Hugh Smith recently opined on how unknowable much of the results of current monetary policy will be, despite the Fed et al's assurances that they have everything well under control:

As noted above, any policy identified as the difference between success and failure must pass a basic test: When the policy is applied, is the outcome predictable? For example, if central banks inject liquidity and buy assets (quantitative easing) in the next financial crisis, will those policies duplicate the results seen in 2008-14?

The current set of fiscal and monetary policies pursued by central banks and states are all based on lessons drawn from the Great Depression of the 1930s. The successful (if slow and uneven) “recovery” since the 2008-09 global financial meltdown is being touted as evidence that the key determinants of success drawn from the Great Depression are still valid: the Keynesian (or neo-Keynesian) policies of massive deficit spending by central states and extreme monetary easing policies by central banks.

Are the present-day conditions identical to those of the Great Depression? If not, then how can anyone conclude that the lessons drawn from that era will be valid in an entirely different set of conditions?

We need only consider Japan’s remarkably unsuccessful 25-year pursuit of these policies to wonder if the outcomes of these sacrosanct monetary and fiscal policies are truly predictable, or whether the key determinants of macro-economic success and failure have yet to be identified.

It's this concern about the failure of the current strategy our central planners are pursuing, paired with the tremendous magnitude of the impending cost of that failure, that motivated Chris to issue our recent report The Consequences Playbook, which begins:

What’s really happened since 2008 is that central banks decided that a little more printing with the possibility of future pain was preferable to immediate pain. Behavioral economics tells us that this is exactly the decision we should always expect from humans. History says as much, too.

It’s just how people are wired. We’ll almost always take immediate gratification over delayed gratification, and similarly choose to defer consequences into the future, especially if there’s even a ridiculously slight chance those consequences won’t materialize.

So instead of noting back in 2008 that it was unwise to have been borrowing at twice the rate of our income growth for the past several decades -- which would have required a lot of very painful belt-tightening -- the decision was made to ‘repair the credit markets’ which is code speak for: ‘keep doing the same thing that got us in trouble in the first place.’

Also known as the ‘kick the can down the road’ strategy, the hoped-for saving grace was always a rapid resumption of organic economic growth. That’s how the central bankers rationalized their actions. They said that saving the banks and markets today was imperative, and that eventually growth would return, thereby justifying all of the new debt layered on to paper-over the current problems.

Of course, they never explained what would happen if that growth did not return. And that’s because the whole plan falls apart without really robust growth to pay for it all.

And by ‘fall apart’ I mean utter wreckage of the bond and equity markets, along with massive institutional and sovereign defaults. That was always the risk, and now we’re at the point where the very last thing holding the entire fictional edifice together is beginning to give way. Finally.

When credibility in central bank omnipotence snaps, buckle up. Risk will get re-priced, markets will fall apart, losses will mount, and politicians will seek someone (anyone, dear God, but them) to blame.

In The Consequences Playbook (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access) we spell out what will happen next and how you should be preparing today for what might happen tomorrow. If you haven't yet read it, you really should. Suffice it to say, a tremendous amount of wealth will be lost if (really, when) the central banks lose control. And standards of living for many will be impacted. A little preparation today can make a huge difference in your future.

Exponential Explosions in Debt, the S&P 500, Crude Oil, Silver and Consumer Prices

by Sprott Money

In 1913 the US national debt was less than $3 Billion, gold was real money, and a cup of coffee cost a nickel.

By 2015 the US national debt had increased to over $18,000,000,000,000 ($18 Trillion), the gold standard was called a “barbarous relic,” most currencies had devolved into fiat paper and digital symbols backed by insolvent governments, and a Grande soy cinnamon latte, double pump, triple shot, extra hot, with sprinkles cost about five bucks.

Debt, money, coffee and prices have changed in 100 years.

What has NOT changed is the inevitable collapse of exponentially growing systems. A few extreme examples of exponential increases are:

- $0.01 (one penny) deposited at the 1st National Bank of Pontius Pilate at 6% interest in the year 15 would be worth approximately $4 Trillion Trillion Trillion Trillion dollars 2000 years later. (Yes, I double checked the numbers, and I used a web based compound interest calculator to triple check. Yes, the number has 48 zeros. Compound interest is the 8th wonder of the world.)

- Promise 1 grain of wheat on the 1st square of a chess board. Promise 2 grains of wheat on the 2nd Then 4 grains on the 3rd square and 8 grains on the 4th square and keep doubling. That promise will consume all the wheat grown in the world long before it gets to the 64th square. (Do you see the similarity between political promises and grains of wheat on chess squares?)

- The US national debt has increased at 9% per year since 1913 and slightly more rapidly since 2008. Assuming the 9% rate continues, the current $18 Trillion in national debt will grow to over $300 Trillion by the year 2065 and to about $6,000 Trillion by the year 2115.

I DOUBT IT!

Exponentially increasing systems cannot last forever. Our problem is that the global financial system is based on exponentially increasing debt, energy usage, population, and exploitation of natural resources. This appears to work nicely, especially for the financial and political elite, in the early years of the exponential increases. However, we are approaching the inevitable end of the exponential increases – perhaps not in a few months – but our systems probably will not last another decade. In the meantime, the plan seems to be “Party On!”

Examine the 30 year chart of the S&P 500 Index (monthly) on a log scale.

- Exponential increases are clearly visible.

- Peaks have occurred about every seven years.

- Rallies and crashes have become more extreme. Look out below!

Examine the 30 year chart for crude oil on a log scale.

- Exponential increases are clearly visible.

- Lows have occurred every five to six years.

- Prices appear ready to rally – maybe not this month or even this year – but I don’t believe prices will stay this low for long when viewed from a 30 year perspective.

Examine the 30 year chart for silver on a log scale.

- Exponential increases are clear and very erratic.

- Important lows have been roughly six years apart.

- Prices look like they have fallen well below the exponential trend, are currently at a cyclic bottom, and have begun a rally. In my opinion, new highs are on the horizon.

CONCLUSIONS:

- Exponentially increasing systems do NOT last forever and become increasingly unstable.

- The current global financial system depends upon “printing” massive quantities of unbacked fiat currency and exponentially increasing debt.

- The exponentially increasing trends for debt, sovereign bonds, currencies, the S&P 500 Index, consumer prices, gold, crude oil, and silver are still in effect. But for how long? What happens at their critical phase transition points?

- The S&P looks like it could roll over at any time.

- Gold and silver appear ready to rally for several more years. Crude oil appears to be finding a bottom and will eventually rally.

- Unstable systems often react violently when they near a critical phase transition or crash point. When the global financial system reaches a phase transition or crash point, would you rather own fiat paper, such as sovereign bonds paying practically nothing and fiat currencies backed by the debt of insolvent entities, or silver and gold?

Repeat: Silver and gold have been a store of value for over 5,000 years. Unbacked paper fiat currencies have always failed. Do you trust politicians and central bankers more than you trust silver and gold? If not, I encourage you to take door # 2 – the one plated with silver on the top and gold on the bottom.

Gold is still undervalued, based on my long-term empirical model, by about 16%. Silver is also undervalued. Unless the President and the US congress slash expenses, actually reduce the national debt, negotiate world peace, and make many other unlikely policy changes, expect silver and gold to rally in a strong up-cycle for several, perhaps many, years.

Debt In The Time Of Wall Street

With all the media focus aimed at Greece, we might be inclined to overlook – deliberately or not – that it is merely one case study, and a very small one at that, of what ails the entire world. The whole globe, and just about all of its 200+ nations, is drowning in debt, and more so every as single day passes. Not only is this process not being halted, it gets progressively, if not exponentially, worse. There are differences between countries in depth, in percentages and other details, but at this point these seem to serve mostly to draw attention away from the ghastly reality. ‘Look at so and so, he’s doing even worse than we are!’

Still, though there are plenty accounting tricks available, you’d be hard put to find even one single nation of any importance that could conceivably ever pay back the debt it’s drowning in. That’s why we’re seeing the global currency war slash race to the bottom of interest rates.

Greece is a prominent example, though, simply because it’s been set up as a test case for how far the world’s leading politicians, central bankers, bankers as well as the wizards behind the various curtains are prepared to go. And that does not bode well for you either, wherever you live. Greece is a test case: ho far can we go?

And I’ve made the comparison before, this is what Naomi Klein describes happened in South America, as perpetrated by the Chicago School and the CIA, in her bestseller Shock Doctrine. We’re watching the experiment, we know the history, and we still sit our asses down on our couches? Doesn’t that simply mean that we get what we deserve?

Here’s McKinsey’s debt report today via Simon Kennedy at Bloomberg:

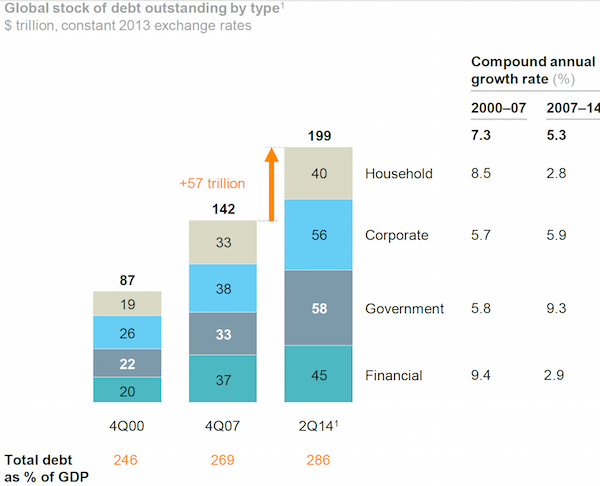

The world economy is still built on debt. That’s the warning today from McKinsey’s research division which estimates that since 2007, the IOUs of governments, companies, households and financial firms in 47 countries has grown by $57 trillion to $199 trillion, a rise equivalent to 17 percentage points of gross domestic product.

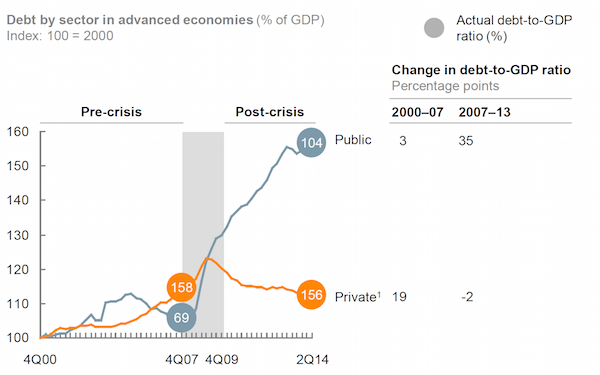

While not as big a gain as the 23 point surge in debt witnessed in the seven years before the financial crisis, the new data make a mockery of the hope that the turmoil and subsequent global recession would put the globe on a more sustainable path. Government debt alone has swelled by $25 trillion over the past seven years and developing economies are responsible for almost half of the overall gain. McKinsey sees little reason to think the trajectory of rising leverage will change any time soon. Here are three areas of particular concern:

1. Debt is too high for either austerity or growth to cure. Politicians will instead need to consider more unorthodox measures such as asset sales, one-off tax hikes and perhaps debt restructuring programs.

2. Households in some nations are still boosting debts. 80% of households have a higher debt than in 2007 including some in northern Europe as well as Canada and Australia.

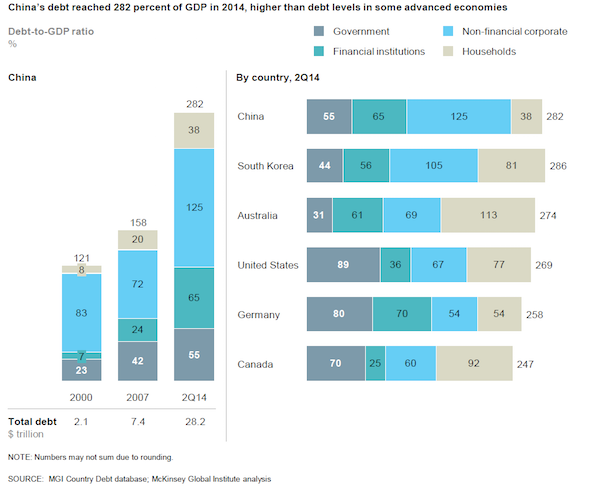

3. China’s debt is rising rapidly. Thanks to real estate and shadow banking, debt in the world’s second-largest economy has quadrupled from $7 trillion in 2007 to $28 trillion in the middle of last year. At 282% of GDP, the debt burden is now larger than that of the U.S. or Germany. Especially worrisome to McKinsey is that half the loans are linked to the cooling property sector.

Note: Chinese total debt rose $20.8 trillion in 7 years, or 281%. And we’re talking about Greece as a problem?! You’d think – make that swear – that perhaps Merkel and her ilk have bigger fish to fry. But maybe they just don’t get it?!

Ambrose has this earlier today, just let the numbers sink in:

Devaluation By China Is The Next Great Risk For A Deflationary World

China is trapped. The Communist authorities have discovered, like the Japanese in the early 1990s and the US in the inter-war years, that they cannot deflate a credit bubble safely. A year of tight money from the People’s Bank and a $250bn crackdown on shadow banking have pushed the Chinese economy close to a debt-deflation crisis. Wednesday’s surprise cut in the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) – the main policy tool – comes in the nick of time. Factory gate deflation has reached -3.3%.

The official gauge of manufacturing fell below the “boom-bust” line to 49.8 in January. Haibin Zhu, from JP Morgan, says the 50-point cut in the RRR from 20% to 19.5% injects roughly $100bn into the system. This will not, in itself, change anything. The average one-year borrowing cost for Chinese companies has risen from zero to 5% in real terms over the past three years as a result of falling inflation.

UBS said the debt-servicing burden for these firms has doubled from 7.5% to 15% of GDP. Yet the cut marks an inflection point. There will undoubtedly be a long series of cuts before China sweats out its hangover from a $26 trillion credit boom. Debt has risen from 100% to 250% of GDP in eight years. By comparison, Japan’s credit growth in the cycle preceding its Lost Decade was 50% of GDP.

Wednesday’s trigger was an amber warning sign in the jobs market. The employment component of the manufacturing survey contracted for the 15th month. Premier Li Keqiang targets jobs – not growth – and the labour market is looking faintly ominous for the first time. Unemployment is supposed to be 4.1%, a make-believe figure. A joint study by the IMF and the International Labour Federation said it is really 6.3% [..]

Whether or not you call it a hard-landing, China is struggling. Home prices fell 4.3% in December. New floor space started has slumped 30% on a three-month basis. This packs a macro-economic punch. A study by Jun Nie and Guangye Cao for the US Federal Reserve said that since 1998 property investment in China has risen from 4% to 15% of GDP, the same level as in Spain at the peak of the “burbuja”. The inventory overhang has risen to 18 months compared with 5.8 in the US.

The property slump is turning into a fiscal squeeze since land sales make up 25% of local government money. Zhiwei Zhang, from Deutsche Bank, says land revenues crashed 21% in the fourth quarter of last year. “The decline of fiscal revenue is the top risk in China and will lead to a sharp slowdown,” he said.

Asia is already in a currency cauldron, eerily like the onset of the 1998 crisis. The Japanese yen has fallen by half against the Chinese yuan since Abenomics burst upon the Pacific Rim. Japanese exporters pocketed the windfall gains of devaluation at first to boost margins. Now they are cutting prices to gain export share, exporting deflation.

This is eroding the wafer-thin profit margins of Chinese companies and tightening monetary conditions into the downturn. David Woo, from Bank of America, says Beijing may be forced to join the currency wars to defend itself, even though this variant of the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” leaves everybody worse off. “We view a meaningful yuan devaluation as a major tail-risk for the global economy,” he said.

If this were to happen, it would send a deflationary impulse worldwide. China spent $5 trillion on fixed investment last year, more than Europe and America combined, increasing its overcapacity in everything from shipping to steels, chemicals and solar panels , to even more unmanageable levels. A yuan devaluation would dump this on everybody else. Such a shock would be extremely hard to combat. Interest rates are already zero across the developed world. Five-year bond yields are negative in six European countries. The 10-year Bund has dropped to 0.31. These are no longer just 14th century lows. They are unprecedented.

[..] .. helicopter money, or “fiscal dominance”, may be dangerous, but not nearly as dangerous as the alternative. China faces a Morton’s Fork. Li Keqiang has been trying for two years to tame the state’s industrial behemoths, and trying to wean the economy off credit. Yet virtuous intent has run into cold reality. It cannot be done. China passed the point of no return five years ago.

That ain’t nothing to laugh at. But still, Malcolm Scott has more for Bloomberg:

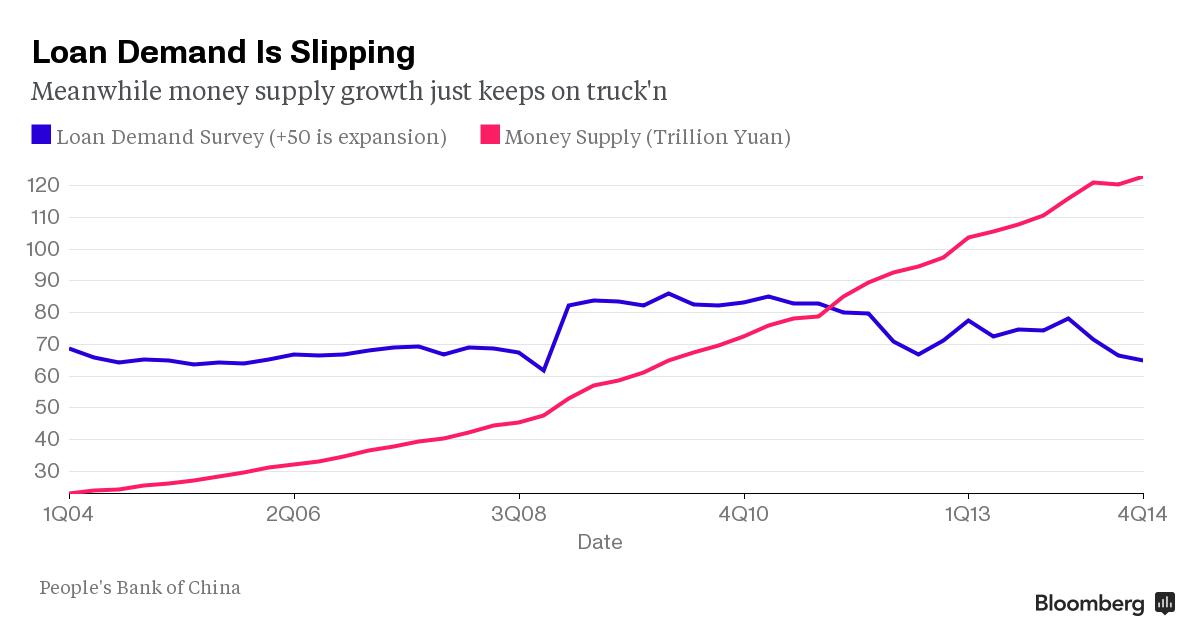

Pushing on a String? Two Charts Showing China’s Dilemma

Is China’s latest monetary easing really going to help? While economists see it freeing up about 600 billion yuan ($96 billion), that assumes businesses and consumers want to borrow. This chart may put some champagne corks back in. It shows demand for credit is waning even as money supply continues its steady climb.

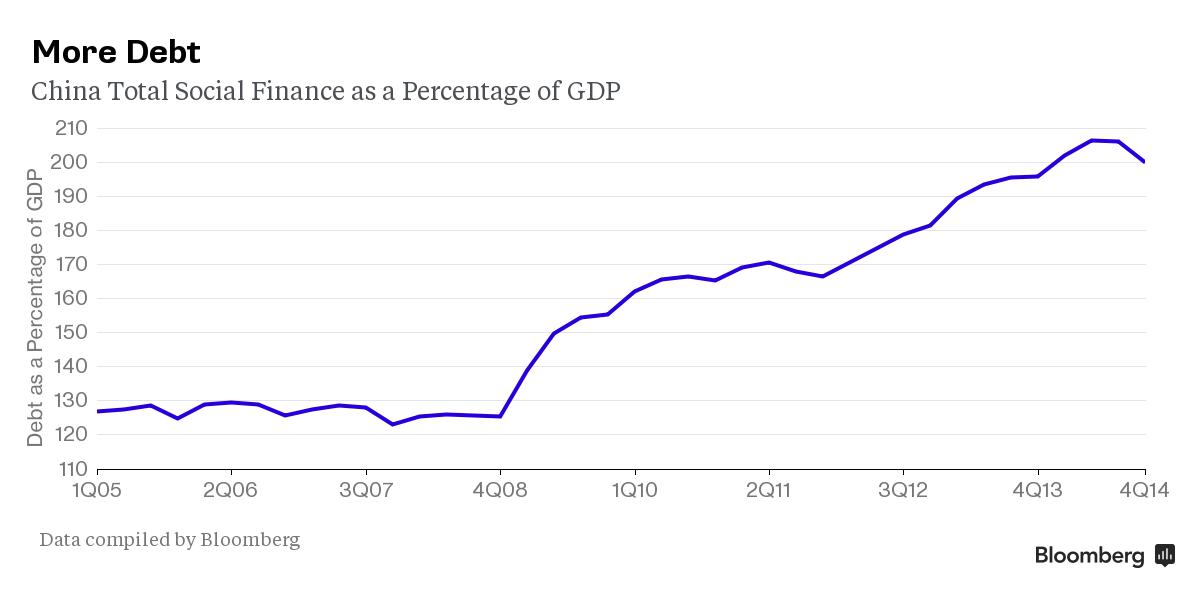

The reserve ratio requirement cut “helps to raise loan supply, but loan demand may remain weak,” said Zhang Zhiwei, chief China economist at Deutsche Bank. “We think the impact on the real economy is positive, but it is not enough to stabilize the economy.” This chart may also give pause. It shows the surge in debt since 2008, which has corresponded with a slowdown in economic growth.

Note: Social finance is, to an extent, just another word for shadow banking.

“Monetary stimulus of the real economy has not worked for several years,” said Derek Scissors, a scholar at the American Enterprises Institute in Washington who focuses on Asia economics. “The obsession with monetary policy is a problem around the world, but only China has a money supply of $20 trillion.”

China now carries $28 trillion in debt, or 282% of its GDP, $20 trillion of which was added in just the past 7 years. It’s also useful to note that it boosted its money supply to $20 trillion. What part of these numbers includes shadow banking, we don’t know – even if social finance can be assumed to include an X amount of shadow funding-. However, there can be no doubt that China’s real debt burden would be significantly higher if and when ‘shadow debt’ would be added.

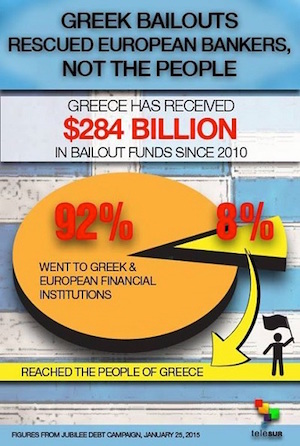

Ergo: whether it’s tiny Greece, or behemoth China, or any given nation in between, they’re all in debt way over their heads. One might be tempted to ponder that debt restructuring would be worth considering. A first step towards that would be to look at who owes what to whom. And, of course, who profits. When it comes to Greece, that’s awfully clear, something you may want to consider next time you think about who’s squeezing who. From the Jubilee Debt Campaign through Telesur:

That doesn’t leave too many questions, does it? As in, who rules this blue planet?! That also tells you why there won’t be any debt restructuring, even though that is exactly what this conundrum calls for. Debt is a power tool. Debt is how the Roman Empire managed to stretch its existence for many years, as it increasingly squeezed the periphery. And then it died anyway. Joe Stiglitz gives it another try, and in the process takes us back to Greece:

A Greek Morality Tale: We Need A Global Debt Restructuring Framework

At the international level, we have not yet created an orderly process for giving countries a fresh start. Since even before the 2008 crisis, the UN, with the support of almost all of the developing and emerging countries, has been seeking to create such a framework. But the US is adamantly opposed; perhaps it wants to reinstitute debtor prisons for over indebted countries’ officials (if so, space may be opening up at Guantánamo Bay).

The idea of bringing back debtors’ prisons may seem far-fetched, but it resonates with current talk of moral hazard and accountability. There is a fear that if Greece is allowed to restructure its debt, it will simply get itself into trouble again, as will others. This is sheer nonsense. Does anyone in their right mind think that any country would willingly put itself through what Greece has gone through, just to get a free ride from its creditors?

If there is a moral hazard, it is on the part of the lenders – especially in the private sector – who have been bailed out repeatedly. If Europe has allowed these debts to move from the private sector to the public sector – a well-established pattern over the past half-century – it is Europe, not Greece, that should bear the consequences. Indeed, Greece’s current plight, including the massive run-up in the debt ratio, is largely the fault of the misguided troika programs foisted on it. So it is not debt restructuring, but its absence, that is “immoral”. </B.\>

There is nothing particularly special about the dilemmas that Greece faces today; many countries have been in the same position. What makes Greece’s problems more difficult to address is the structure of the eurozone: monetary union implies that member states cannot devalue their way out of trouble, yet the modicum of European solidarity that must accompany this loss of policy flexibility simply is not there.

You can put it down to technical or structural issues, but down the line none of that will convince me. Who cares about talking about technical shit when people are suffering, without access to doctors, and/or dying, in a first world nation like Greece, just so Angela Merkel and Mario Draghi and Jeroen Dijsselbloem can get their way?

Oh, no, wait, that graph there says it’s not them, it’s Wall Street that gets their way. It’s the world’s TBTF banks (they gave themselves that label) that get to call the shots on who lives in Greece and who does not. And they will never ever allow for any meaningful debt restructuring to take place. Which means they also call the shots on who lives in Berlin and New York and Tokyo and who does not. Did I mention Beijing, Shanghai, LA, Paris and your town?

Greece’s problem can only be truly solved if large scale debt restructuring is accepted and executed. But that would initiate a chain of events that would bring down the bloated zombie that is Wall Street. And it just so happens that this zombie rules the planet.

We are all addicted to the zombie. It allows us to fool ourselves into thinking we are doing well – well, sort of -, but the longer term implications of that behavior will be devastating. We’re all going to be Greece, that’s inevitable. It’s not some maybe thing. The only thing that keeps us from realizing that is that the big media outlets have become part of the same industry that Wall Street, and the governments it controls, have full control over.

And that in turn says something about the importance of what Yanis Varoufakis and Syriza are trying to accomplish. They’re taking the battle to the finance empire. And it should not be a lonely fight. Because if the international Wall Street banks succeed in Greece, some theater eerily uncomfortably near you will be next. That is cast in stone.

As for the title, it’s obviously Marquez, and what better link is there than Wall Street and cholera?

Greece: Are You Finally Ready to Do the Right Thing and Leave the Euro?

by Charles Hugh Smith

The era of living off borrowed money is over in Greece, and the Greek people now have a choice.

Almost four years ago I wrote Greece, Please Do The Right Thing: Default Now (June 1, 2011). Default remains the only real way forward for Greece and Europe.Consider the destructive "gains" reaped by four years of lies, predation, debt-serfdom and austerity in service to kleptocrats: tremendous suffering by many Greek citizens, all for nothing but propping up the evil of debt-serfdom to the Greek kleptocracy and the financial royalty of Europe.

The truth is Greece squandered four years propping up a patently false illusion that using the euro as a currency was worth everything, when it was always worth nothing. As I have described at length for four long years, the euro created a brief (and highly profitable to the kleptocrats and banks) fantasy that marginal borrowers would magically be transformed into solid credit risks simply because they were now borrowing euros instead of drachmas.

It doesn't matter what is being borrowed--euros, drachmas, quatloos or beads--marginal borrowers are still high credit risks. The entire subprime mortgage fiasco was based on a similar financial fraud: that the housing bubble would enable homeowners with insufficient cash, income and creditworthiness to service gargantuan mortgages--mortgages that were issued with the intent of defrauding buyers of mortgage-backed securities.

Greece is simply an example of the same fraud played out on a larger stage.

The euro is one of the greatest monetary frauds in history, and its managers have waged one of the greatest campaigns of financial terrorism in history. These managers have persuaded (or bamboozled) the majority of Greeks (if polls are to be believed) and just about everyone else on the planet that exiting the euro would be an unmitigated disaster for the Greek people.

This is absolutely opposite of the truth: exiting the euro and returning to its own sovereign currency will be the greatest possible good for the Greek people, for the simple reasons that 1) they will finally be in control of their own destiny and 2) issuing one's own currency disciplines the entire economy in positive ways.

Ask yourself who is more likely to succeed in the world: the spoiled child who lacks even the most basic self-discipline, or the child who has learned that actions today have long-term consequences?

It's not that difficult to lay out a fiscal and monetary plan that would quickly build trust in a new Greek currency. The hard part is breaking the cycle of corruption and lies that is the Status Quo in the Greek economy.

1. Announce that the government can only spend what it collects in taxes and fees. The state will not borrow money, period.

2. Announce a new, simplified tax structure, with tax rates far below those of other European nations. For example, if the value-added tax (VAT) is 17% elsewhere in Europe, the Greek rate would be set at 7%. (Compare that to the sales tax in California, which is 9%.)

3. Explain that the future of Greece depends entirely on everyone paying taxes, since the government will no longer borrow-and-spend.

3. Hire 10,000 currently unemployed accountants (including recent college graduates who have been unable to find jobs in accounting), train them in forensic accounting and auditing and unleash them on the Greek economy, starting with the top 1/10th of 1% (the kleptocracy class) and working their way down to the corner cafe.

3. Make the pain of cheating and non-compliance higher than the pain of paying relatively low taxes.

4. Change the social perception that not paying taxes is acceptable behavior. Publicize the list of tax cheats, etc.

5. Make government spending transparent and auditable by any citizen with an Internet connection.

6. Enforce strict banking laws where lenders that loan money without regard for risk management are forced to absorb their losses and close their doors. Encourage prudent private lending and borrowing.

A nation's currency is a measure of global trust in that nation's fiscal and monetary order. If that order is based on a culture of corruption, lies, fraud and debt, the currency will lose value: why own a currency that is constantly being debased by lies and unpayable debts?

A currency based on transparency, fiscal prudence, little state debt and strictly enforced taxation and risk management will gain trust and value. The people who fear a Greek currency are actually afraid that the current culture of corruption, tax evasion and lies cannot be transformed. They are wrong. That culture can be transformed by strict adherence to simple rules of transparency, low tax rates, prudent state spending and a private banking sector that is held accountable for its risk management (or lack thereof).

In sum, the era of living off borrowed money is over in Greece, and the Greek people now have a choice: they can continue down the path of poverty by leaving their culture of corruption unchanged, or they can grasp the nettle and support a new culture based on transparency, fiscal prudence and strict adherence to the basic rules of monetary management.

Se la Grecia riparte dai derivati

Il piano che il ministro delle Finanze greco illustra ai leader europei in questi giorni prevede la conversione di parte del debito in titoli indicizzati alla crescita del paese. La proposta avrebbe diversi vantaggi, ma la sua realizzazione è ostacolata da una grave difficoltà tecnica.

I DERIVATI NELLA VALIGIA DEL MINISTRO

Uno spettro si aggira per l’Europa: l’ingegneria finanziaria.

Il ministro delle Finanze greco, Yannis Varoufakis, gira l’Europa proponendo un pacchetto di ristrutturazione del debito basato su due punti. Il primo è la conversione del debito verso il vecchio fondo salva-stati Efsf e gli altri paesi europei in titoli di debito indicizzati alla crescita dell’economia (growth bond). Il secondo è la conversione dell’esposizione verso la Bce in titoli irredimibili.

Mentre i titoli irredimibili ci riportano ai secoli passati, e alla preistoria della finanza, la proposta dei titoli indicizzati alla crescita è, appunto, ingegneria finanziaria. Ma l’idea è particolarmente interessante e merita un approfondimento sia sui vantaggi che sulle difficoltà di attuazione.

Prima di tutto, però, è il caso di ricordare che stiamo parlando di una proposta che riguarda l’involucro di un progetto di ripresa per la Grecia, piuttosto che il progetto stesso. In altri termini, il ministro Varoufakis sta mostrando ai paesi europei un abito senza l’indicazione dell’evento per il quale verrà indossato. E l’incuranza con cui sceglie la propria mise per incontrare i suoi interlocutori sembra essere una metafora della sua proposta finanziaria: i titoli indicizzati alla crescita come un vestito comodo, adatto per ogni occasione. La descrizione del progetto per la crescita della Grecia verrà dopo.

Questa riflessione ci consente di spiegare la dissonanza apparente di un ministro di estrema sinistra che in tenuta casual va a offrire derivati (perché di questo stiamo parlando) ai potenti di Europa. E la dissonanza sembra ancora più profonda se consideriamo che la crisi del debito sovrano europeo era partita dalla Grecia per l’utilizzo di derivati a fini di manipolazione contabile: ora ne viene proposta la soluzione ancora attraverso l’utilizzo dei derivati e ancora a partire dalla Grecia.

Ma la dissonanza è solo apparente, perché stavolta i derivati sono a fin di bene.

LO STRANO CASO DEI TITOLI INDICIZZATI ALLA CRESCITA

I titoli indicizzati alla crescita del Pil hanno avuto un destino strano. Il principio che li ispira è semplice: il pagamento di cedole e capitale è legato alla crescita del Pil, con varie formule. Maggiore la crescita, maggiori i pagamenti. Sono comparsi nel 2005, come parte del pacchetto di ri-negoziazione del debito argentino, seguito al default del 2001 e in quella struttura di swap del debito svolgevano solo il ruolo di comparsa. Nella proposta greca, invece, questi titoli avrebbero il ruolo da protagonista e sarebbero proposti in una rinegoziazione con investitori sovrani anziché privati.

Il destino dei growth bond è strano perché sono stati studiati, all’indomani del caso argentino, con grande attenzione dal Fondo monetario internazionale, che era notoriamente a favore di emissioni di titoli di questo tipo da parte dei paesi in via di sviluppo.

Con queste premesse, colpisce che questa forma di indicizzazione non sia diventata uno strumento adottato dal Fondo stesso. Infatti, proprio nel caso di finanziamenti dell’Fmi, condizionati allo svolgimento di “compiti a casa”, questi prodotti avrebbero rappresentato un incentivo credibile alla definizione di piani di aiuto realistici e orientati alla crescita: se l’Fmi avesse proposto politiche di sviluppo inefficaci, ci avrebbe rimesso di tasca sua. Invece, la scelta di caldeggiare la soluzione, ma solo per i crediti degli altri, non ha fornito un segnale propriamente credibile ai mercati.

LA RIDUZIONE DEL RISCHIO

Nella proposta del ministro delle Finanze greco, l’aspetto di incentivo verso i creditori della Troika non è ovviamente presente, perché uno dei punti centrali del piano è il superamento del ruolo della Troika, la fine del suo potere. Ma i growth bond sono un abito che si adatta anche per questa occasione. Vengono proposti alle controparti come strumenti per la riduzione del rischio.

Il meccanismo di riduzione del rischio è sottile, ma può essere spiegato partendo dalla considerazione che i titoli indicizzati alla crescita del Pil sono una sequenza di derivati: nel nostro caso, sono opzioni sulla crescita del Pil greco. Quando acquistiamo un derivato siamo in generale esposti al rischio che la controparte fallisca. Qui la peculiarità, rispetto al rischio di credito di un normale titolo, consiste nel fatto che l’esposizione alla perdita non è data , ma è legata al particolare scenario di valore del derivato quando si verifica il default. Nel caso di eventuali growth bond greci, l’esposizione alla perdita da un default della Grecia dipenderebbe dallo scenario di crescita futura del Pil greco.

Una conclusione naturale di questo ragionamento è che una determinante rilevante del rischio di controparte è data dalla correlazione tra probabilità di default ed esposizione. Se l’esposizione al rischio è più alta quando si verifica il default, il rischio di credito sarà più elevato: è quello che nel rischio di controparte in derivati si chiama “wrong way risk”. Nel caso dei growth bond succede esattamente l’opposto. La riduzione del rischio di credito deriva dal fatto che in questo caso l’esposizione ha una naturale correlazione di segno negativo con il default, e gioca a favore dell’investitore. In concreto, un tasso di crescita del Pil più alto è associato, ceteris paribus, a una probabilità di default più bassa. Se quindi il tasso di crescita atteso del Pil è più alto, il valore della perdita in caso di default (l’esposizione) è più alta, e la probabilità di default è più bassa. Se invece il tasso di crescita è basso, la probabilità di un default sarà più alta, ma il valore dell’esposizione sarà basso. Potremmo chiamare questo effetto “right way risk”, come uno dei pochi casi in cui la correlazione gioca a favore dell’investitore, procurando una copertura “naturale” del rischio di credito. Lo stesso effetto si verifica per i titoli indicizzati all’inflazione.

La proposta di Yannis Varoufakis ha quindi il notevole pregio di fornire ai creditori una protezione dal default superiore a quella dei titoli attuali. Non ha invece alcun carattere di incentivo, come avrebbe invece avuto la stessa proposta fatta dalla Troika. In parole povere, il messaggio di Varoufakis è: la crescita della Grecia è compito di un programma elaborato dai greci; i titoli indicizzati alla crescita vi daranno maggiori guadagni se il programma riesce e vi proteggeranno (parzialmente) dai danni del default in caso contrario.

In linea di principio, il piano è condivisibile. In pratica, la sua realizzazione è legata a una grossa difficoltà tecnica: come assicurare l’equivalenza finanziaria tra i nuovi titoli e quelli esistenti.

Se venissi incaricato di fare i conti, mi mancherebbero due ingredienti difficilmente reperibili: i) la distribuzione di probabilità del tasso di crescita greco; ii) la correlazione tra tasso di crescita del Pil e rischio di default della Grecia. Poiché un mercato di riferimento per estrarre informazioni su questo non c’è (come c’è invece per l’Argentina), si aprirebbe uno strano mercato tra investitori sovrani, forse affiancato da un “mercato grigio” di banche di investimento che potrebbero proporre quotazioni per i growth bond di futura emissione.

Il rischio è che potrebbe rientrare dalla finestra il sospetto che lo scambio possa nascondere un haircut di fatto, con una valutazione a favore della Grecia o un’ulteriore deprivazione della Grecia se il prezzo fosse a favore delle controparti. E il problema ritorna alla domanda centrale della letteratura dei derivati: qual è il fair value?